Author Beth Macy

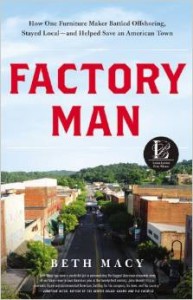

I’m button-popping proud to present journalist Beth Macy, whose new book Factory Man: How One Furniture Maker Battled Offshoring, Stayed Local — and Helped Save an American Town, comes out today. It’s a story of family, feuding, grit, gumption, pride, war and furniture. The book, which has been getting rave reviews, is Beth’s first, but you can bet the farm that it won’t be her last.

Me: As a newspaper reporter, you’ve done in-depth stories before, but you’ve never gone in depth to the tune of 582 pages. Aside from the obvious word-count difference, what are some of the differences between this type of journalism and daily newspaper journalism?

Beth: The planning was the biggest undertaking — and by that I mean the three months it took me and my agent to get the book proposal, including a 27-chapter outline, into shape before submitting it to publishers. I followed that loose outline religiously, though some of the facts changed as my reporting turned up new details and twists. Having the rough outline storyboarded like that afforded me the opportunity to focus close-in on the chapter I was working on at the time, which was freeing. I had the entire outline written on Wizard Wall (office supply nerd alert!) on an entire wall of my office. And I kept a white board next to my desk with notes for the chapter I was working on, plus a column on the left for ideas that came to me for the subsequent chapter. Between digital documents (interview notes, copious e-mails and court-case archives) and paper documents (in books, magazine and newspaper articles), I probably had 1,000+ different sources to comb through. Command-F on my iMac desktop was a constant companion; it was hard to remember what I’d named all my files. I need a better system for my next book!

Beth: The planning was the biggest undertaking — and by that I mean the three months it took me and my agent to get the book proposal, including a 27-chapter outline, into shape before submitting it to publishers. I followed that loose outline religiously, though some of the facts changed as my reporting turned up new details and twists. Having the rough outline storyboarded like that afforded me the opportunity to focus close-in on the chapter I was working on at the time, which was freeing. I had the entire outline written on Wizard Wall (office supply nerd alert!) on an entire wall of my office. And I kept a white board next to my desk with notes for the chapter I was working on, plus a column on the left for ideas that came to me for the subsequent chapter. Between digital documents (interview notes, copious e-mails and court-case archives) and paper documents (in books, magazine and newspaper articles), I probably had 1,000+ different sources to comb through. Command-F on my iMac desktop was a constant companion; it was hard to remember what I’d named all my files. I need a better system for my next book!

Me: I’ll ask a similar question about cultivating sources: I recall your saying you’d talked to John Basset III (the chairman of Vaughan-Bassett Furniture Co. and the book’s central character) more than 300 times on the phone alone. What was it like to go back to him that many times?

Beth with JBIII -- still speaking.

Beth: This is a hilarious question because I maybe called him five times out of the 300. It was — just about all of our communication — very much on his time: nights, weekends, daytime. Whenever he felt like calling me, he did. This entitled sense of timing is a huge part of his personality, though, and I was able to understand it better as I personally experienced it. I kept a list of questions I needed to ask him handy because I knew that usually a day wouldn’t pass before he’d call me again. We visited in person maybe a dozen times, including at his home and his factory.

Me: Did you ever have a point during the publishing process where you thought: This just isn’t going to happen?

Beth: No. Funny thing about an advance: They pay you, and you have to produce — or else you have to give it back, and that’s a very productivity-inspiring thing! I knew I had the bones of the story going in because I’d already written a pretty extensive 5,000 word newspaper article on JBIII. The more interviews I did and the deeper it went, the story just got richer and richer, and I became more excited about the material. I was overwhelmed at times by the scope of it — try to cover 110 years, with business practices spanning the globe — but mostly the more I learned, the juicier it got.

Me: What was the most difficult hurdle in writing this book?

Beth: Getting the CEOs who’d closed factories to talk to me. Most of them said no, including (initially) Rob Spilman of Bassett Furniture. I’d seen this great interview with George Packer on The Daily Show after his amazing book, “The Unwinding,” came out last year. And he actually made a quip about not wanting to talk to the CEOs in his book because he didn’t want them to become human to him. I thought, Amen! Then one of my best friends, a reporter visiting from Boston, convinced me that I needed to lay out all my cards with Spilman and convince him to talk. Because the book was as much, maybe even more, about what happened to Bassett, Va., as to Galax, and if I wanted to be fair and nuanced then I needed Rob’s perspective. He had a story to tell, too, and she advised being as transparent with him as possible about what I was trying to do.

A relative eventually intervened on my behalf, and I asked Rob a fourth (or whatever it was) time, and he finally relented to two lengthy interviews and several fact-checking sessions by phone and e-mail. He ended up giving me some of the best material in the book — including hilariously damning anecdotes about his father (stabbing the suckling pig and shouting “Larry Moh!”), poignant scenes about the closures, and important insights behind the company’s major shift to retail when imports hit and the factories closed. I’m grateful to him for talking to me, but I don’t expect he’s going to embrace the book because he believes the people and the town need to move on from the losses and not “sit around and cry in our beer.”

But a lot of people I talked to aren’t yet ready to move on from the losses. Many are still hurting, still looking for work. To move on, those losses first need to be acknowledged.

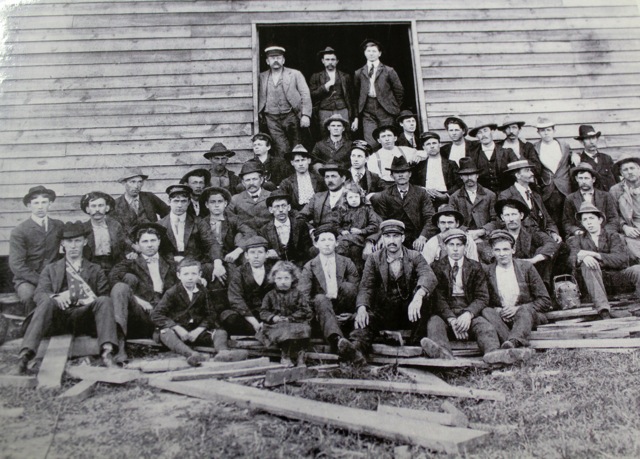

"The first known photo of Bassett Furniture Industries, circa 1902, wherein a wily saw miller named J.D. Bassett Sr. and his brother set out to swipe furniture-making from Michigan and New York and turn all that Reconstruction-era cheap labor and free trees into a furniture-making dynasty." (Quotes from Beth Macy)

Me: Has your research for Factory Man changed your shopping habits at all? In what way?

Beth: Our dishwasher broke last year, and when we finally got around to replacing it, we researched our options and chose a Maytag replacement because it was made in a Kentucky factory and was exactly what we wanted. (The price was comparable to the imports.) I go out of my way, buying clothes, to shop at local boutiques that carry made-in-America items, and I always thank the owners for providing that option. I made an attempt to buy Christmas presents for everybody with made-in-America items, but that was waylaid by the teenagers who wanted electronics and a new cellphone – neither of which were made domestically. When the older boy went off to his first college apartment and took his bed with him, we turned his room into a guest room and bought made-in-Galax Vaughan-Bassett Furniture from a local store. I know intimately now that there are real people and real livelihoods at stake at the other end of a consumer purchase.

When I asked the Surabaya furniture engineers at PT Romi if they ever thought about the American workers they displaced, they giggled and said no. “But I do worry every year about the future of the factory, that someone somewhere else cheaper will start to do it, and that will be that for us,” a man named Fachrudin said.

Me: For this story, you traveled through the hinterlands of Virginia and North Carolina and into Asia. At which spot/moment did you feel the most out of your element?

Beth: In Virginia and North Carolina, I did interviews anywhere I could convince people to talk to me, from libraries and employment commission waiting rooms to trailers, farmers markets and nursing-home rooms. I was a little nervous about going to Indonesia because the last time I’d been in a developing country — Haiti, post earthquake, in 2011 — I found myself smack in the middle of both a cholera epidemic and a cholera-incited riot. It was truly a life-threatening situation, though ultimately we were fine. We were fine in Indonesia, too, though we were at the mercy of the company, Stanley Furniture, which was allowing us to see some (but not all) of the factories where its furniture is made. People were lovely to us, but we were also advised not to travel alone without a guide, and security guards at our hotels routinely checked the under-carriage of our vehicles for bombs. [Husband] Tom [Landon] went with me to shoot pictures and take video. We would have preferred to have gotten more on the ground level — visiting workers in their homes, for instance — but we didn’t have the time or budget to pull that off. We briefly talked to some human rights workers and journalists on our own, but most of our visit to Surabaya was coordinated by the Stanley employees, who were actually quite open and generous.

Stanley Furniture allowed us to tour three of the factories in Surabaya where their furniture is now made. Indonesia has a rich history of craft furniture-making, but in recent years several large-scale factories have opened to take advantage of rising wages in China, drawing many former subsistence farmers into work who are eager to join the cash economy. Elok Andrea (far right), 26, fed a machine in the rough end of a spawning factory called Multimanao, and told me it was her first time being paid for work. “Here we have roof,” she said, explaining why she prefers factory work to farming.

Me: Talk a little about your own family’s factory experience.

Beth: I dedicate this book to all the world’s factory workers, especially my mom, who soldered airplane lights when the economy was good and babysat when it wasn’t. I grew up in a factory town not unlike Galax, and I experienced the vagaries of the shifting economy firsthand. When work was scarce, my parents talked about the possibility of our heat being cut off. So when a laid-off Stanley Furniture gave me her mother’s phone number because her own was about to be cut off, I knew exactly how that felt.

Me: And also talk a little, if you would, about the choice to be a first person narrator in this story.

Beth: I wanted this book to be transparent. I tell people right at the start I’m a factory worker’s daughter because to have hidden that very relevant fact (as we do so often in newspaper articles) would have been disingenuous. Jimmy Breslin wrote that empathy is the key to human understanding, which is what my longtime newspaper editor Brian Kelley calls my “superpower.” I get people to open up because I don’t hold anything back — I tell them where I’m going with the story and I tell them how I feel, no bullshit or tricks. You can’t fake it.

From the very beginning, my agent and I envisioned this book to be tonally and structurally akin to a Michael Lewis or Tracy Kidder book, including first-person insights when relevant to the story. In Kidder’s biography of Paul Farmer, for instance, some of the most revealing details were exchanges between the two. Another model was “The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks,” wherein part of the tension of the book is: Will the descendants of Lacks open up to author Rebecca Skloot in her search? It didn’t hurt that John Bassett and I were very different (in our upbringings) and very alike (underdogs of a sort), providing lots of contrast and narrative juice. Some of the most revealing things about his character — from his dirty jokes to his constant phone calls to his fiery temper — were more effectively described from a first-person point of view.

Me: I laughed out loud at colloquialisms like: “Morale was lower than a snake’s butt in a wagon rut.” Or JBIII’s “Nervous as a whore in church.” Any favorites?

Beth: “Mister Ed didn’t cull up and down the Smith River.” I loved that because it was so very local, particular not just to one person but also to one part of Henry County. And also because everyone I ran into who was familiar with Bassett Furniture between the ‘50s and ‘70s knew exactly what it meant! I also loved another Mister Ed-ism: “There’s no water in the swamp.” When I fell into the ice-cold Smith River in the epilogue of the book and finally crawled my way up the poison ivy-covered banks, I immediately thought: Mister Ed, wherever he is, is loving this – sweet revenge!

Me: How about other use of “colorful language,” since that’s something as newspaper journalists we often have to lose. (I distinctly recall one reporter’s outrage when the copydesk changed his “balls” to “courage.”)

Beth: The precise words people use say a lot about them. So if Little Brown was game with me using the words my interviewees really said — and my editor there was, without a single exception — I was too. Furniture-making is sweaty, hard work, and the people making it and the people (mainly men) overseeing the people making it cuss a lot. Loud and colorfully. They just do! When one of my sources shook his head and lamented the pervasive bad behavior and language, calling it “the Smith River twitch,” I thought: This is language gold.

Me: As someone who recalls being taught “always name the dog,” I especially loved the story about Cindy and Jill, JBIII’s hunting dogs, and the way that made him real.

Beth: The Bassetts are huge dog people. One of the first things you notice when you pull into their driveway is that their entire side yard is covered with animal gravestones. The first time I visited, JBIII spent 15 minutes talking about Jill, after pointing her headstone out, and then I saw that huge beautiful formal portrait of him in the sitting room with those two hunting dogs. It was easy to put together the parallel between how he’d inspired competition among his hunting dogs and his employees, but I was much more familiar with factory work than I was grouse-hunting and peppered him with lots of questions about hunting – which he found strange – until my analogy felt firm.

Me: Do you think that the way you grew up – without much money and with a mother working in a factory – gave you an advantage/street cred in telling this story?

Beth: It gave me street cred with the displaced workers for sure because, face it, I’m just more comfortable talking to regular people than I am CEOs. One of my sisters and my brother have worked in factories, and my nephew works in a factory now (alas, as a temp employee).

Me: In the end, do you think JBIII did finally trust you? What was his reaction to the book?

Beth: It’s a tenuous kind of trust. His reaction to an early draft we let him read for fact-checking purposes was mixed, and tempers flared on my side and his after his initial burst of anger related to some facts I included that he found snarky.

And while we’ve patched things up since that come-to-Jesus, I’ve noticed he’s eager to receive the final version of the book to make sure the changes he was most fired-up about were made. (Most were, though he’s still mad that I refused to enumerate his “five points for completing in a global marketplace” as a stand-alone feature in the book.) I don’t think he trusts me entirely, which I understand but I also find tiring. I’ve been as transparent with him as I have the line workers. I have to add, though, that I appreciate that he led me to people he knew would say bad things about him — in the interest of making sure all sides were covered. He didn’t ask me to change a single thing that other people said bad about him, including the oft-repeated line, “He’s an asshole!” Most people would have had trouble with that, but he owned it and reveled in it.

Me: I actually got teary at the last lines of this epilogue. When did you think of the ending for the story?

Beth: The epilogue is actually my favorite part. I had thought all along that the book would end with John’s triumphant reopening of the vacant plant next door in Galax. But on the way back from one of my last reporting trips to Bassett, I knew I had to end it there. (How did I know that? Because I found myself unexpectedly in tears. I’ve been doing this kind of reporting long enough to know that tears, more than anything, must be heeded!)

The book’s hero was in Galax, but the predominant economic story was of displacement. So it had to end in Bassett. After reading my first draft, my editor, John Parsley, sent me back one more time to search out Mary Hunter’s grave, an assignment that turned into a boon for the epilogue. And while my favorite source in the book — librarian Pat Ross — helped me find the grave, that afternoon she drove me to meet the factory gravedigger who presented me with a gift that became the basis for the final scene.

I wanted to echo that earlier quote from Mary Redd about the snake because, to me, her sentiment embodied a desire that was still so palpable among the displaced workers I’d met. When she said it, it took my breath away. It was nothing but raw truth. It deserved to be the final word.

Thanks, Beth, for taking the time to answer my questions!

Beth used to sit across from me at The Roanoke Times. We’ve both since left the paper — Beth just two months ago so she could work on her next book — but I like to think that we’re still coworkers; our seats are just farther apart. If you’d like to learn more about her and the making of this book, which I trust will make newspaper headlines in November or April, you can visit her author page on Facebook, check out her blog and website, follow her on twitter at @papergirlmacy, or view some of the behind-the-scenes films her husband, Tom, produced. (The first one is here.) You could also just put up your feet and drink a Factory Girl beer, inspired by Beth’s book.

It is!! Moreso for people who will recognize every landmark.

Going to Barns and Noble this morning to get my copy. Will read it here in Orlando.then back home to Galax for her book signing Saturday at the Chestnut Creek School of the Arts. Exciting!